As you can see, the theory of reflective practice assumes that in developing our professional practice we encounter unexpected situations and make mistakes. You can have different attitudes and behaviours towards mistakes. You can ignore them, try to cover them up, beat yourself up or you can choose to learn from them. The first two reactions are a breach of your obligations under the Code of Conduct and beating yourself up is not very productive. The truth is that most practitioners do in fact reflect when they make a mistake, when they are less than happy with an outcome, or when they encounter an unexpected behaviour or situation in practice. However, this reflection is not always done systematically. By reflecting systematically on our experience, we can create maps to learn from our mistakes and from the uncertainty and anxieties inherent in professional practice. Those maps will then help us react and respond appropriately when unexpected situations occur again.

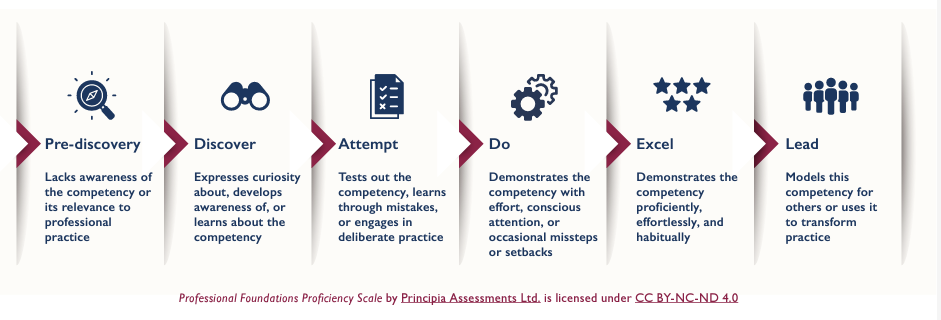

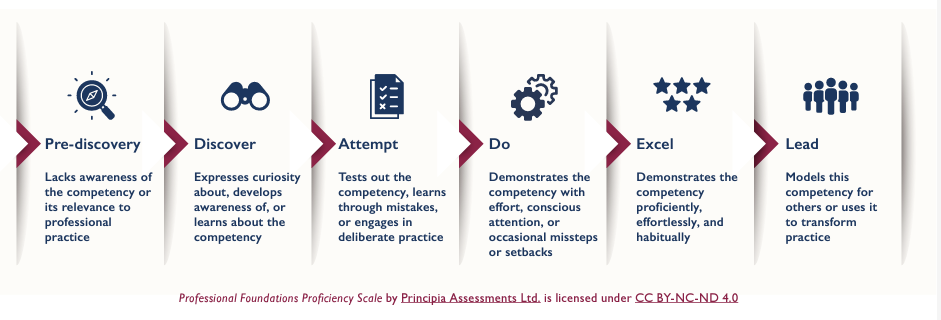

Reflection is therefore necessary in gaining and maintaining competence and moving from doing to excelling. You did not excel in your law practice at the start. It takes years of experience, but also the discipline of reflecting on that experience, to develop theories about how to practice law well. Further, Michael Lang explains that practice without a commitment to learning from experience is incomplete and will never produce mastery, because repetition without reflection tends to produce mechanical responses and poses a risk that bad habits become practice. Additionally, without a commitment to learning from experience, there is no opportunity for improvement and self-correction, and mistakes can get ignored or minimized.

The proficiency scale (depicted below) that accompanies the Profile and is included in the Tool is intended to help you assess your current proficiency levels in various competencies and to set goals to improve or enhance those proficiency levels. For any competency selected from the Profile or elsewhere, different proficiency levels are expected at various career stages and in various practice areas or settings. It is up to you to determine how to best improve proficiency in your chosen areas of professional development, depending on your level of experience, practice context and goals.

The key to reflective

practice is rigour and being systematic. As Donald Schön put it,

“Reflection

is not an invitation to woolly-headedness, a never-never land where anything

goes”.

(Schön,

1991, at 10)

As author Michael Lang writes, reflective

practice is more than “savoring a success or lamenting a frustrating

experience”, comparing notes with a colleague, or writing case notes or

summaries. The process of reflecting on practice is conscious, purposeful and

systematic. As Lang puts it,

“Reflective practice is

a means for thoughtfully and introspectively examining professional actions and

then, through self-assessment, learning to enhance our abilities and skills.”

(Lang,

2019, at 15)

Sherwood

and Horton-Deutsch explain how reflective practice contributes to a

transformational change process:

“Reflective practice used as a

systematic way to ‘make sense of experience’ can be the avenue to promote

practice improvements and satisfaction in our work. In this sense, reflective

practice becomes a transformative change process by which we can improve

practice, refocus our work, and increase meaning and satisfaction from work

well done…”

(Sherwood & Horton-Deutsch, 2017, at

5)

Curiosity

and the intention to learn must be present for reflective practice. An

objective of reflective practice is self-awareness, in order to improve

professional practice.

As you can see,

reflective practice is as much a mindset or attitude as it is a skill or process.

It becomes a “way of being” in practice and in the world, both professionally

and personally.

In the next section,

we’ll explore some different types of reflective practice.